Art Museums and Indigenous Repatriations

View full PDF: Framing Cultural Patrimony as Art

Introduction

The United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement, also known as ICE, features a page on their website dedicated to Cultural Property, Art and Antiquities (CPPA) Investigations. The site describes Homeland Security special agents’ responsibilities to investigate and prosecute the importation and distribution of stolen or looted cultural property, with the stated goal of “…dismantling [of] transnational criminal organizations, including those that may use cultural property trafficking to launder money and fund terrorist activities.” 1 Additional training on proper identification and handling of cultural property is provided to agents by the Smithsonian Institution.

The agency boasts an extensive list of artifacts seized at or shortly after entering the U.S. boarder: “U.S. repatriates pre-Columbian Mayan artifact to Guatemalan government”, “Vase seized from Getty museum returned to Italy”, “Ancient alabaster stele goes home to Yemen after criminal investigation”. From 525 million-year-old Chinese fossils to Peruvian skulls to Paul Klee paintings, Homeland Security agents have repatriated more than 20,000 artifacts to over 40 international institutions since 2007. 2 The agency continues, “Cultural heritage is finite and irreplaceable…once a piece of history is destroyed, it is lost to the world forever. Once a cultural property investigation is complete, the CPAA Program coordinates the return or repatriation of the object or artifact to its rightful owner, often in a formal ceremony.” 3

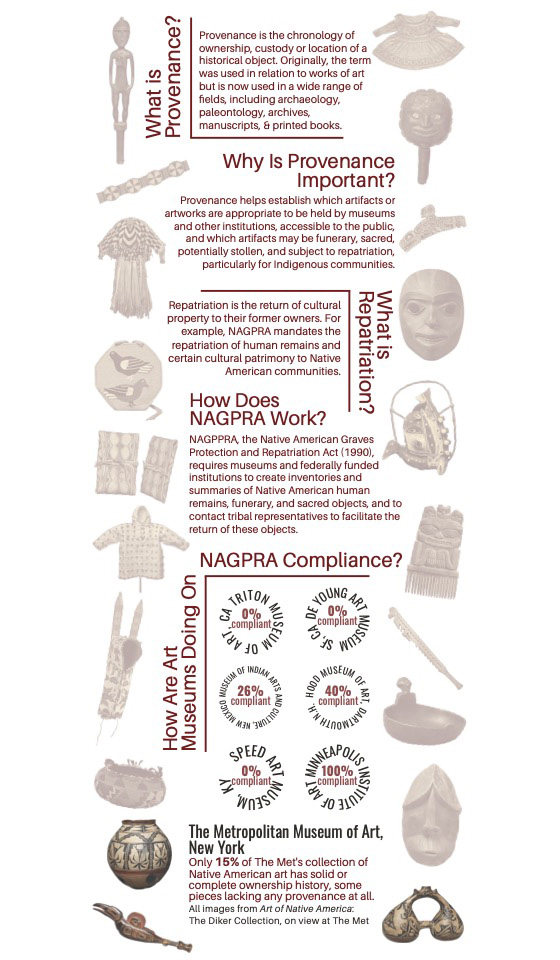

While ICE identifies only nations and institutions as rightful owners of cultural heritage material, the language on their website describes those who steal or traffic cultural heritage material in criminal terms, even linking them to forms of terrorism. However, as of October of this year, more than half of reported Native American human remains and about thirty percent of reported Native American funerary objects held by federally funded institutions across the country have yet to be made available for return to tribal communities.4 The Museum Act of 1989, a precursor to much of the legislative framework for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act established the following year, was spurred when Northern Cheyenne leaders found out that nearly 18,500 human remains were housed within the Smithsonian Institution. The law required the Smithsonian to create an extensive inventory of the remains and funerary objects and to notify affiliated communities promptly to coordinate their return.5

1 “Cultural Property, Art and Antiquities (CPAA) Investigations” U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Department of Homeland Security, last modified April 14, 2023, https://www.ice.gov/factsheets/cultural-artifacts.

2 ibid.

3 ibid.

4 “Native American Priorities: Protection and Repatriation of Human Remains and Other Cultural Items” U.S. Government Accountability Office, published Oct 10, 2023, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-106870.

5 Jack F. Trope and Walter R. Echo-Hawk, The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act: Background and Legislative History, Arizona State Law Journal, 24:35 (1992): 54-57.